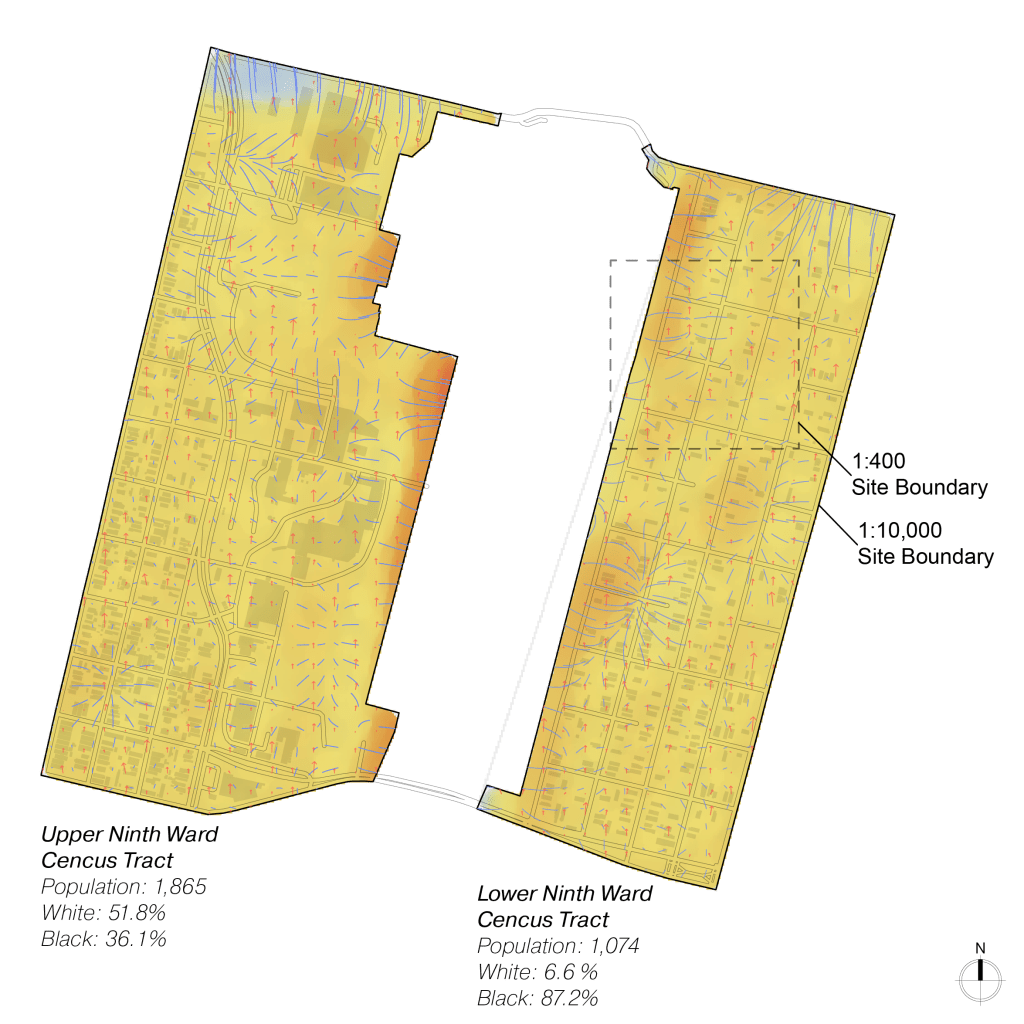

This project observes and provides a new model approach to the reoccurring hydrological disasters in New Orleans, Louisiana through a lens of major and minor. Research exploring the economic consequence of hydrological risk fueled by climate change through the years to 2050 predicts that droughts, floods and storms could wipe 5.6 trillion USD from the GDP of key economies, with some more affected than others. Through the lens of major and minor, we have studied precedent events of hydrological disasters. We defined these ‘Deleuzian’ terms as major being an arborescent view and minor being a rhizomatic view. Major is a binary method of reason, in contrast where minor is non-binary. These methods of thinking take place amongst groups with majoritarian people exploiting minoritarian for its personal agenda. Census data reveals that the Lower Ninth Ward is 50% more black populated than the Upper Ninth Ward. The minoritarian Lower Ninth Ward was impacted the most by Hurricane Katrina. Post disaster left a distraught neighborhood destroyed by the breached infrastructure. The levees within this community serve the majoritarian by allowing capital to reach New Orleans via carbon extraction. These same levees are the infrastructure which, in turn, deterritorialized the minor communities it was to protect. Our design team drew various modalities of flooding and unflooding across several urban fabrics. This resulted in uncovering the code and strata that these hydrological disasters operate within. Using these characteristics of disaster, we built an atlas that adapts by deterritorialized the stratified landscape impost by the major and territorializing the smooth space to elevate back to a safe datum above sea level.

Repetition of natural disasters is something we as architects design for. Deleuze has many arguments regarding time and its receptiveness to repetition; defining repetition as a prior identical model of time. He proposes three models of time: time as a circle, time as a straight line, and time as difference and repetition. The first two models look at time with difference and repetition being a secondary process to the primary process of time. The third model looks at time as primary processes of difference and repetition. “.. it has the power of expression and not of form, that it has repetition as power, not symmetry as form. Indeed, it is through symmetry that rectilinear systems limit repetition, preventing infinite progression and maintaining the organic domination of a central point with radiating lines, as in reflected or star-shaped figures. It is free action, however, which by its essence unleashes the power of repetition as a machinic force that multiplies its effect and pursues an infinite movement.” –Deleuze, “A Thousand Plateaus”.

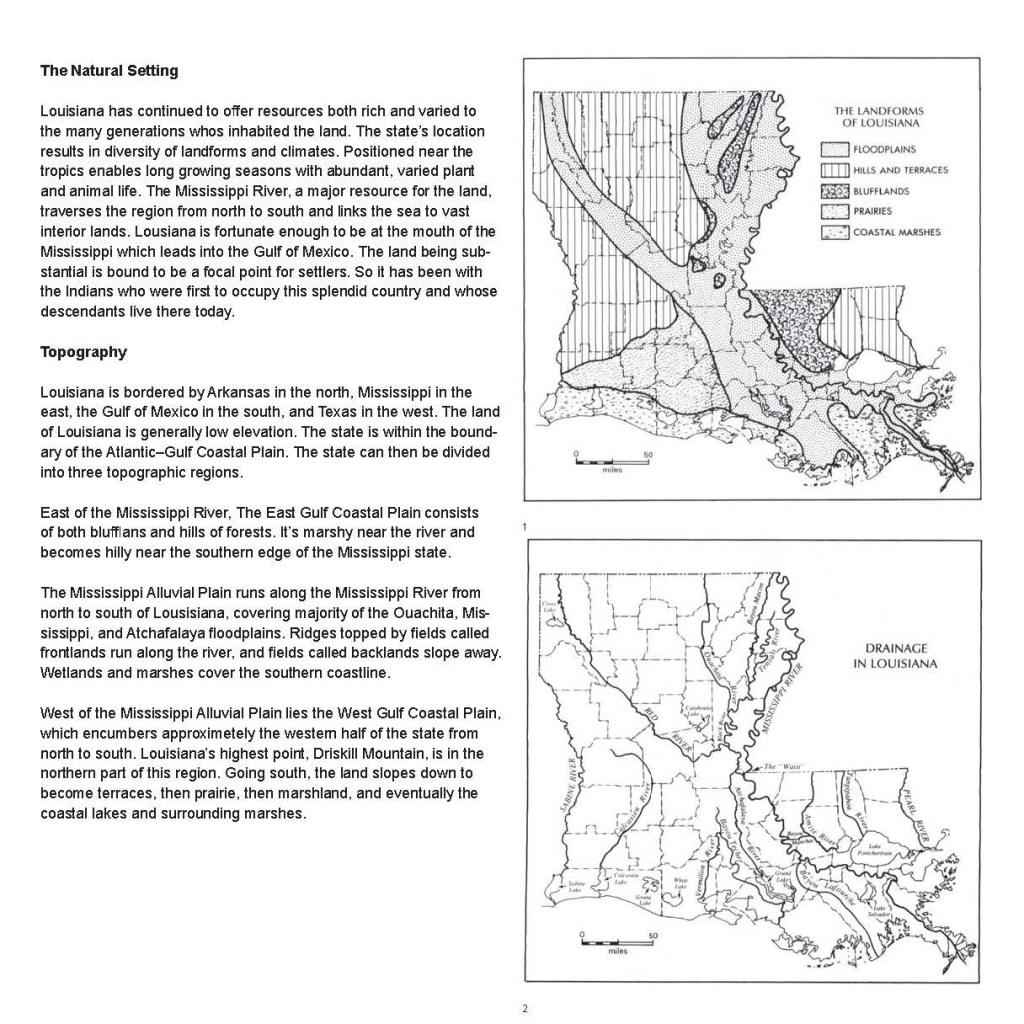

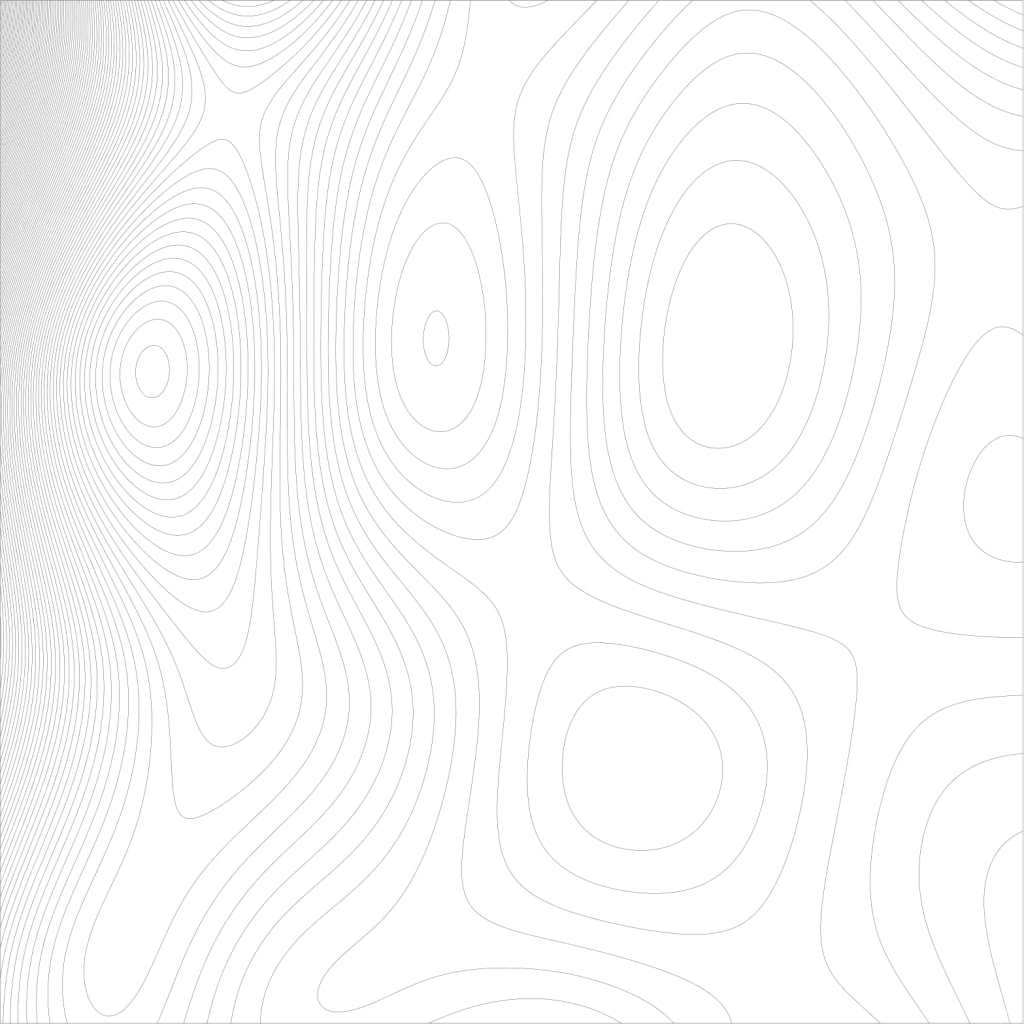

New Orleans has a lot to do with the processes of time. For thousands of years, since the era of the ice age, the Mississippi River was a transportation device for sediment from the northern plains and pouring into the Gulf of Mexico. That sediment accumulated where the Mississippi river meets the Gulf of Mexico. It was that sediment that created the land of New Orleans. Every spring the Mississippi River would flood, dumping more sediment until New Orleans was far above sea level. The city of New Orleans began development in the 1800s, and as 100% of the land was above sea level, majority of the perimeters were swamp land. As New Orleans continues development, engineers created pumping systems to dry out the swamps, allowing New Orleans to continue its expansion. As of 1895, approximately 5% of New Orleans was below sea level. By 1935, it increased to 30%. As of today, 50% of more is below sea level, where experts consider the city as a bowl waiting to turn into a lake. When the wetlands and swamps were dried, the groundwater lowered, the soil dries out, and organic matter decays. Air pockets were created beneath the surface and the surface substrate began to settle/consolidate, thus dropping below sea level. The sediment would continue to flood New Orleans; however, engineers have created dams to trap river sediment, and levees to prevent flooding.

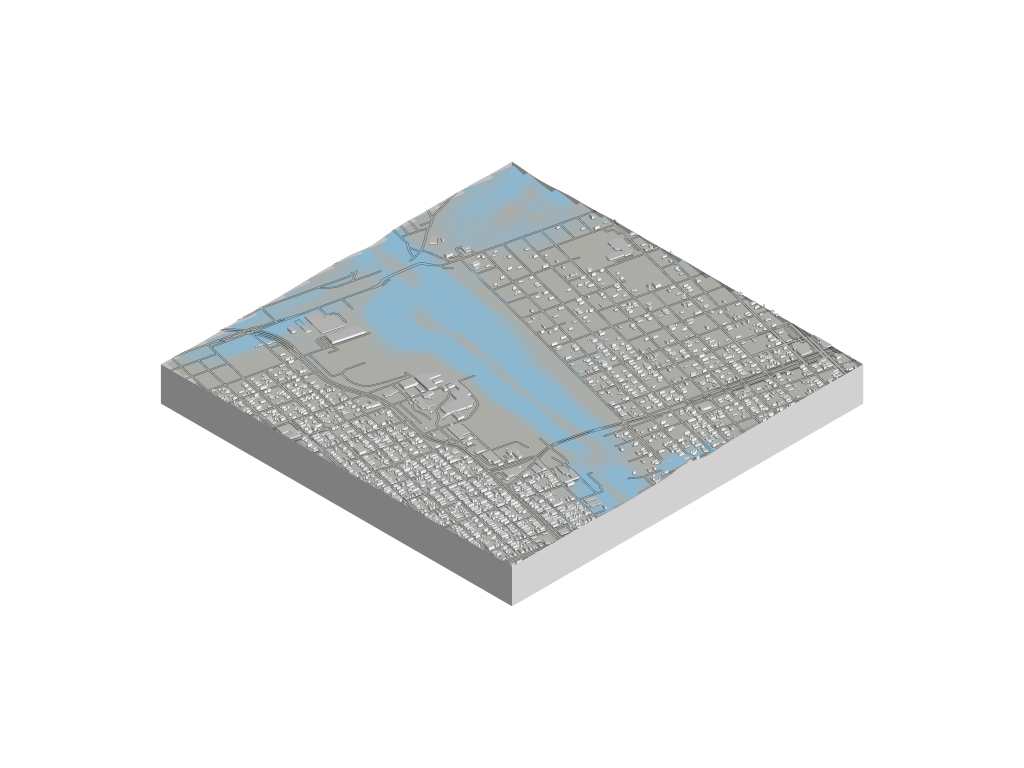

When Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans on August 29, 2005, the infrastructure failed to protect the city boundary and the disaster unfolded. Water rushed into new Orleans from whatever angle it could breach the levee walls. One small neighborhood, the Lower Ninth Ward, located to the east of the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal (IHNC), was flooded the most due to the inadequate design of the levee walls in this area.

At a current rate, New Orleans is dropping about 2 inches each year, on average. In contrast, sea levels are also rising due to a warming climate forcing engineers to build levee walls higher. This is the battle of state major against nature minor. Or is it the other way around? The state’s civilization of the lower ninth ward, once protected by the 12-foot levee walls, now diluted by nature. But as the water recedes, revealing a footprint of sediment. It is clear as mud, who will win this battle. Nature is only revealing what it was intended to do in the first place.

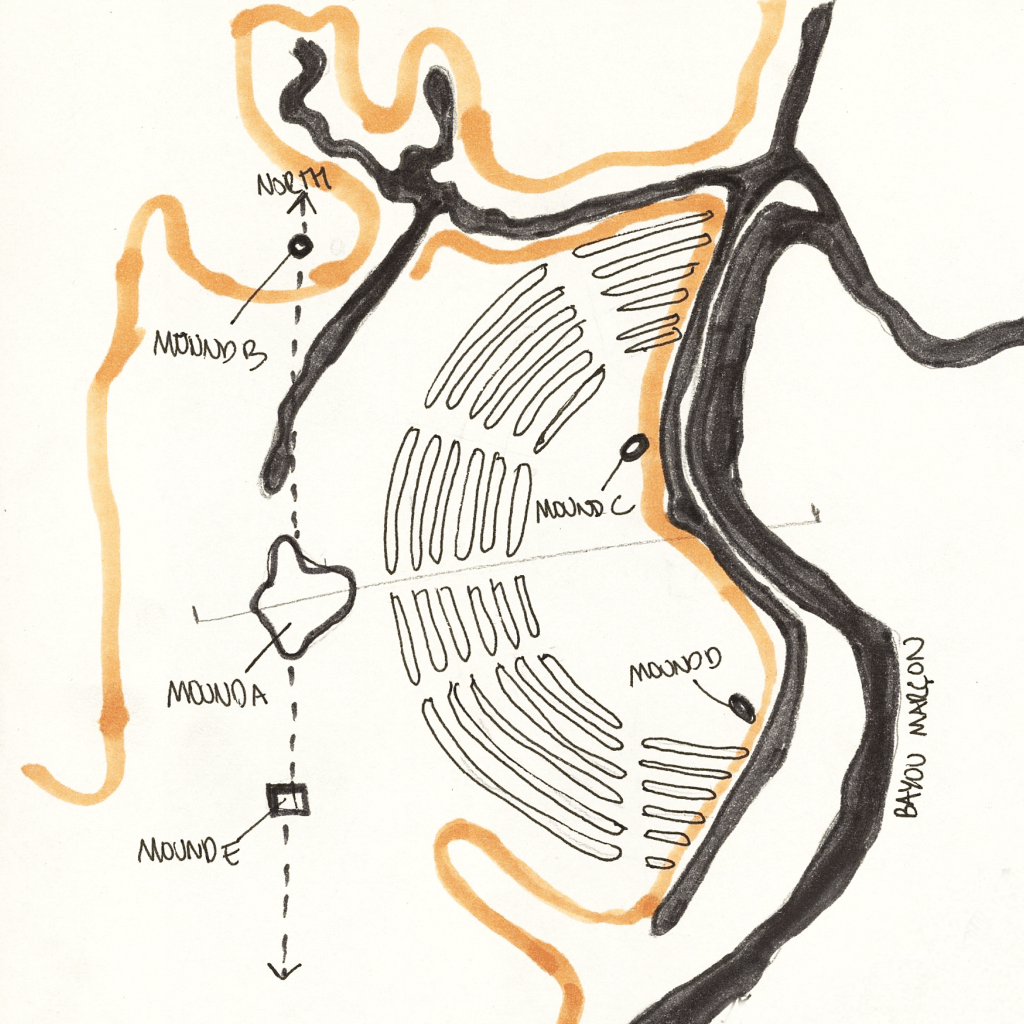

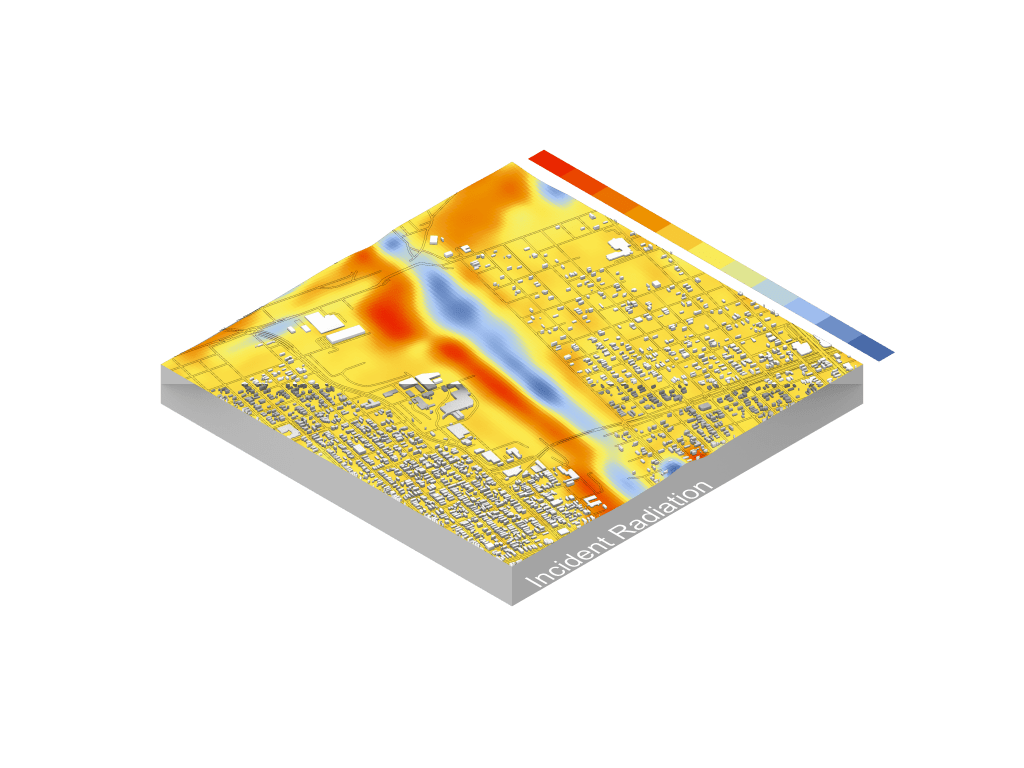

For thousands of years, Native Americans have lived along the Mississippi River and its tributaries as hunter-gatherers or prolific agricultural and urban civilizations. Their way of life understood the rhizomatic relationships between the land and the environment as intrinsically intertwined with human development and well-being. This ancient adaptive system of collective nomadic intelligence became forgotten, as the arrival of European explorers, then settlers territorialized the land and its preliminary intelligence, deeming it minor language and establishing a major sedentary language. As the state territorialized the Mississippi River Basin with its arborescent way of thinking, these major state powers began to extract resources from the land and code a system of socioeconomic problems that are still in place today. In the process of crystallizing sedentary modes of thinking onto a newly stratified space, state power dynamics established what Deleuze refers to as the major and minor. With the states appropriation of the nomad through Manifest Destiny, it began to territorialize the western tributaries of the Mississippi. The agency of the Mississippi River Basin created a transportation artery for agricultural and industrial goods, with the first steamboat occupying its waterways by 1811. Since then, the state began to code major and minor power dynamics as it stratified the land. These socioeconomic disparities became amplified as the substantial growth of cities and larger ships began the construction of massive engineering works such as levees, locks and dams in order to further extract resources from the rich fertile landscape. This established a new carbon form coded into the striated land that benefits major agricultural production, which has crystalized a system of drainage among the water basin that prevents the natural flow of its newly polluted waterways and accelerates hydrological natural “disasters” that disproportionally affect communities. Poverty Point is an example of the earthworks and systems that the natives created to live amongst the flooding. Located in Louisiana, these earth mounds are the remains of an ancient city constructed 34 hundred years ago. Home to 4 to 5 thousand indigenous people, evidence suggests that these mounds were quickly erected. Learning from the natural phenomena of the Mississippi, we can begin to predict how the behavior of levees, floodways, banks and river speed respond to the shape of the river, which is dictated by elevation, width and depth. Discovering this intelligence allows for the collection of sediments and the rewilding of New Orleans through indigenous techniques. Learning from the Nantchez Tribe, we can utilize native low-tech materials to build thermal masses using wattle and daub assemblies. Furthermore, these wattle and daub assemblies become arranged to create enclosures that responds to the hot and humid climates of Louisiana. Understanding the relationship between the environment, sun and humanoid. Harnessing the thermal mass of baked clay balls, indigenous communities learned to store excess heat through thermal masses in order to cook

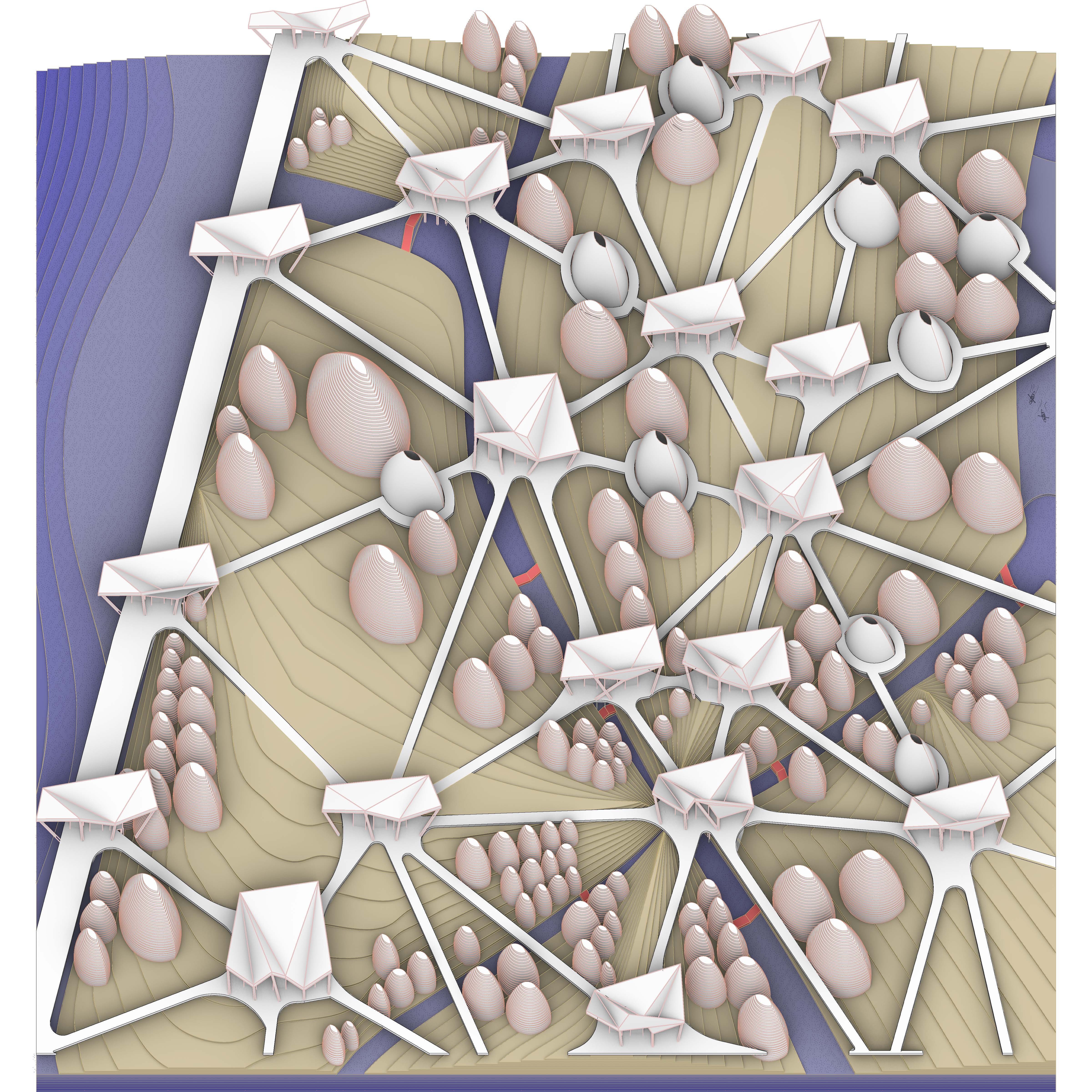

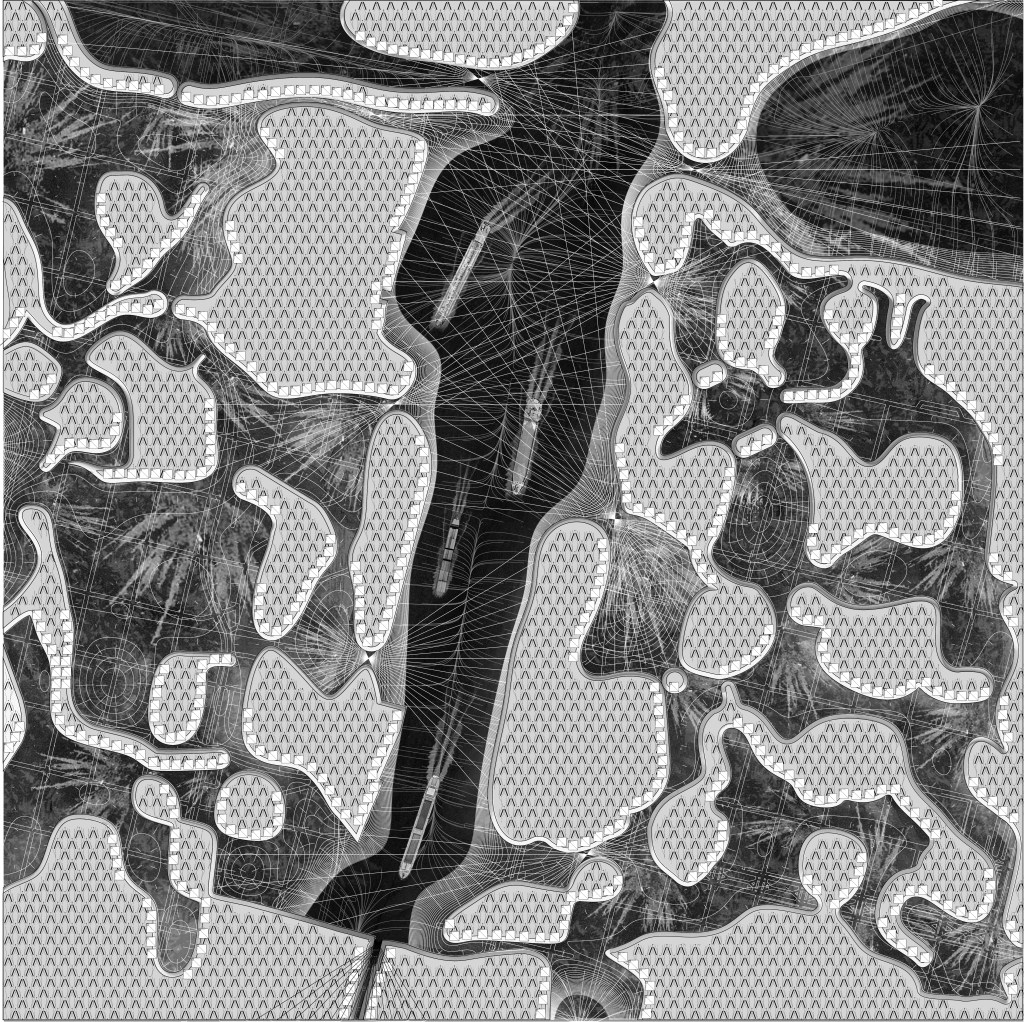

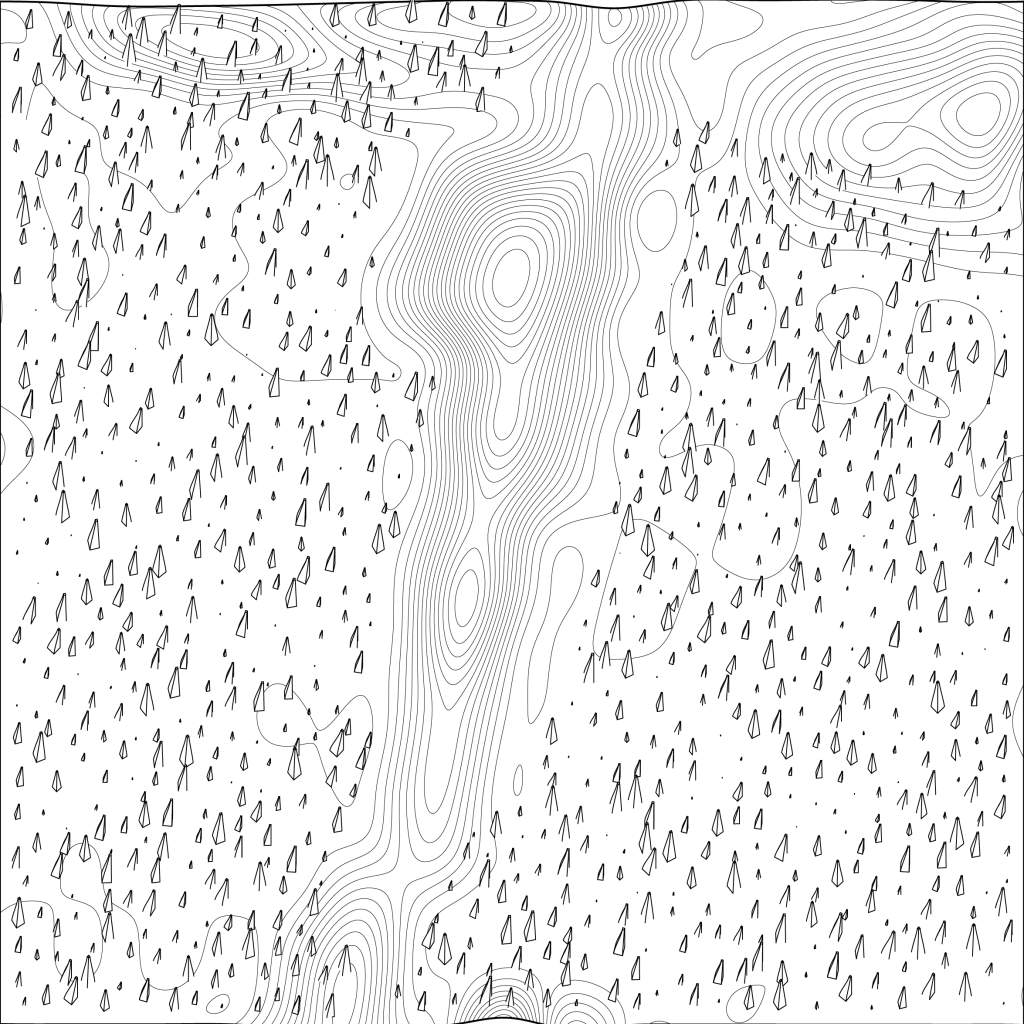

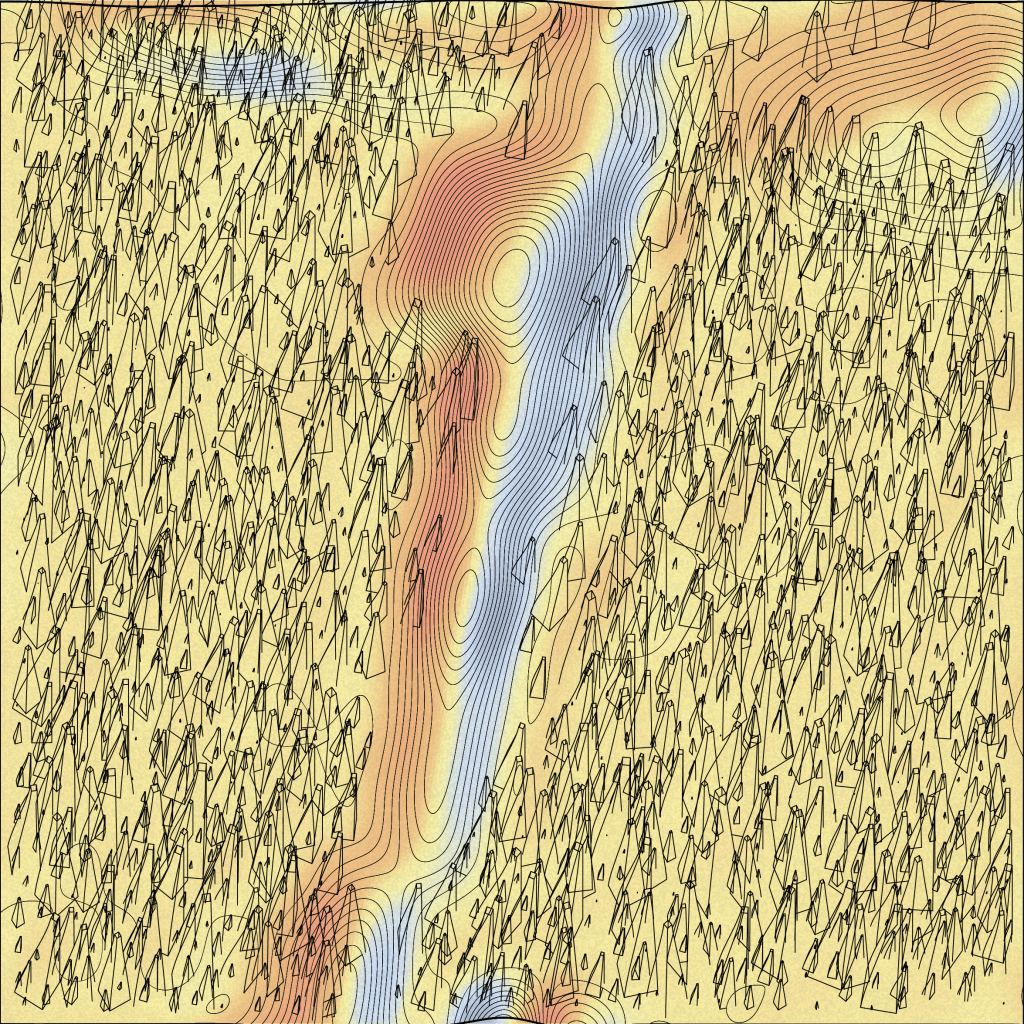

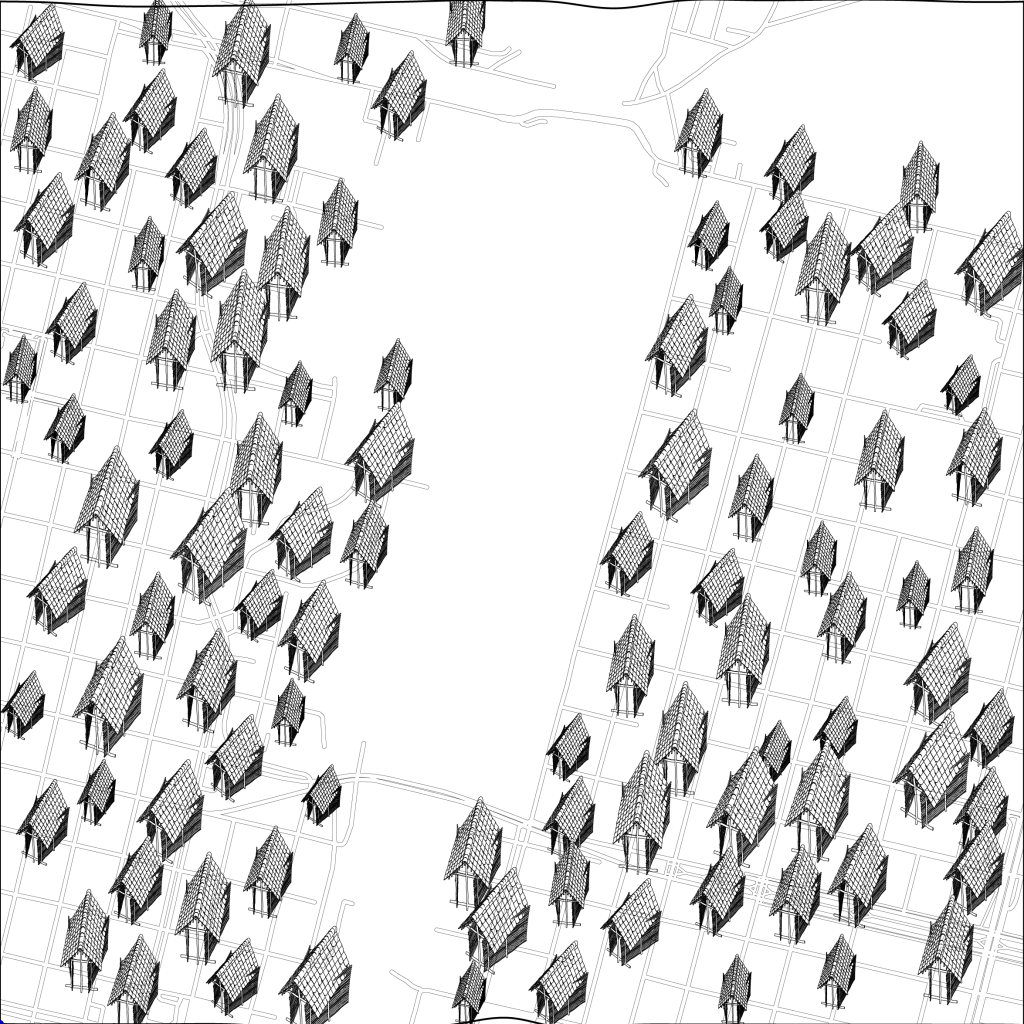

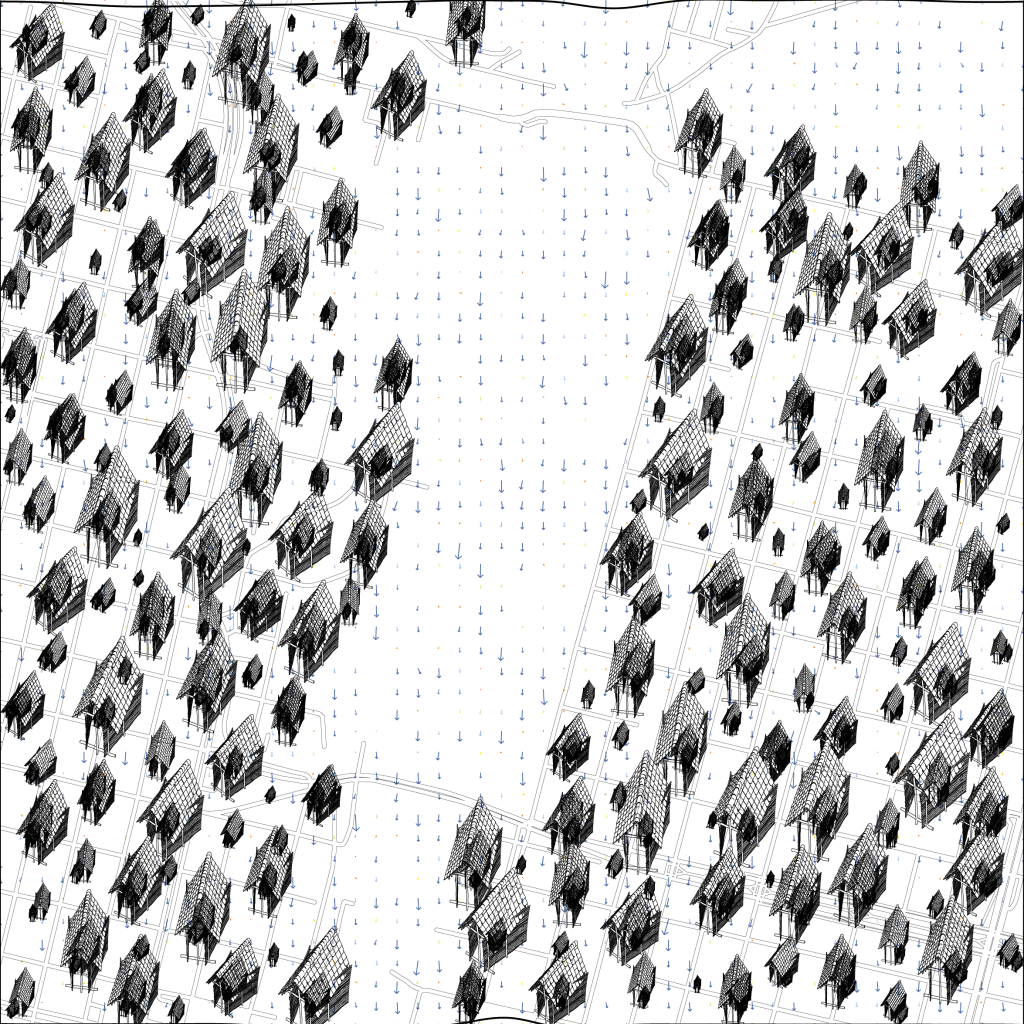

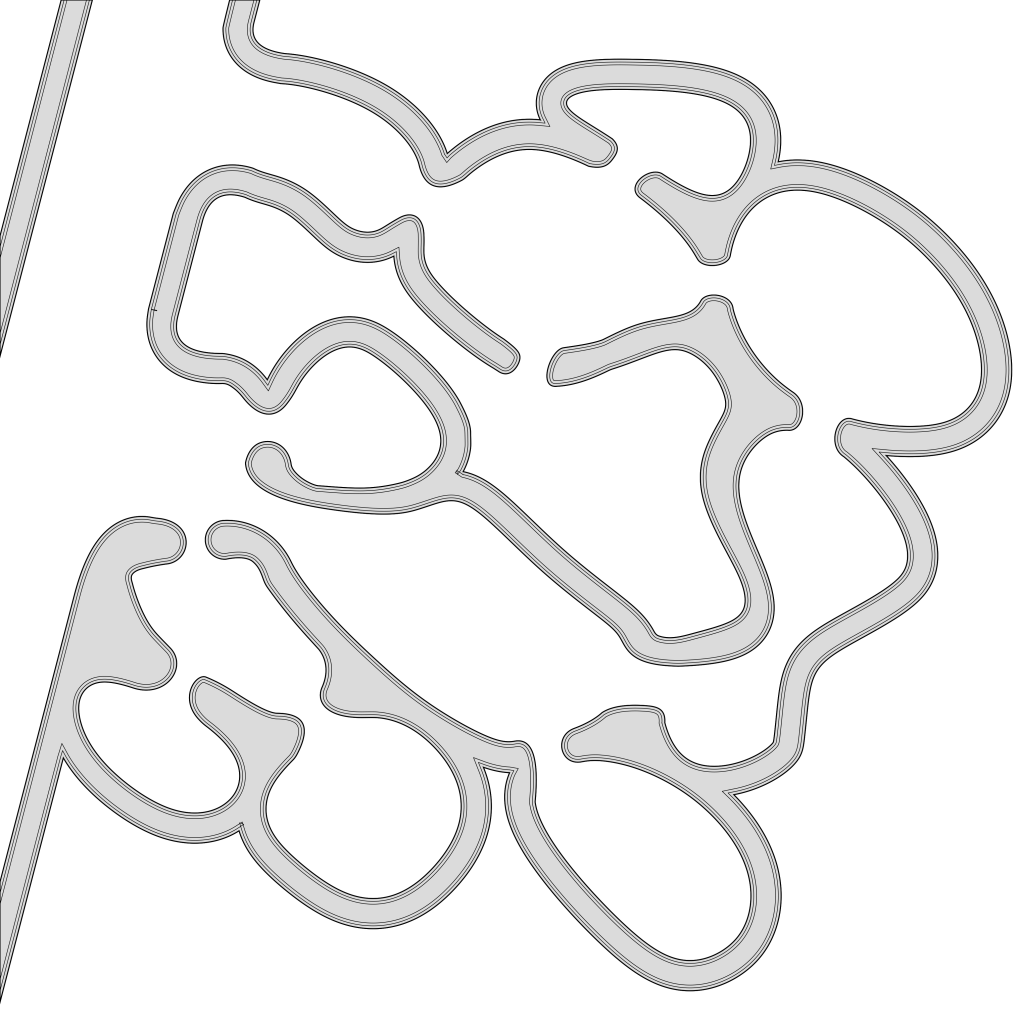

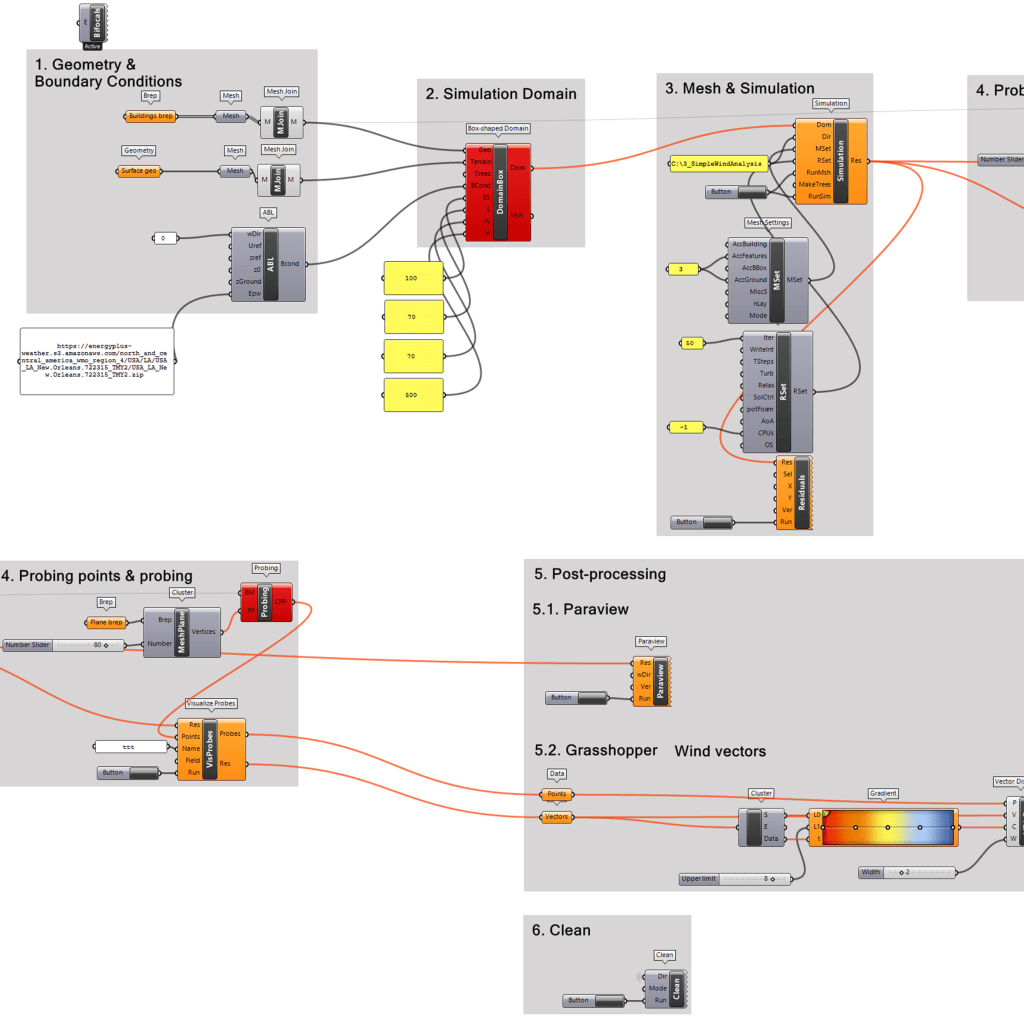

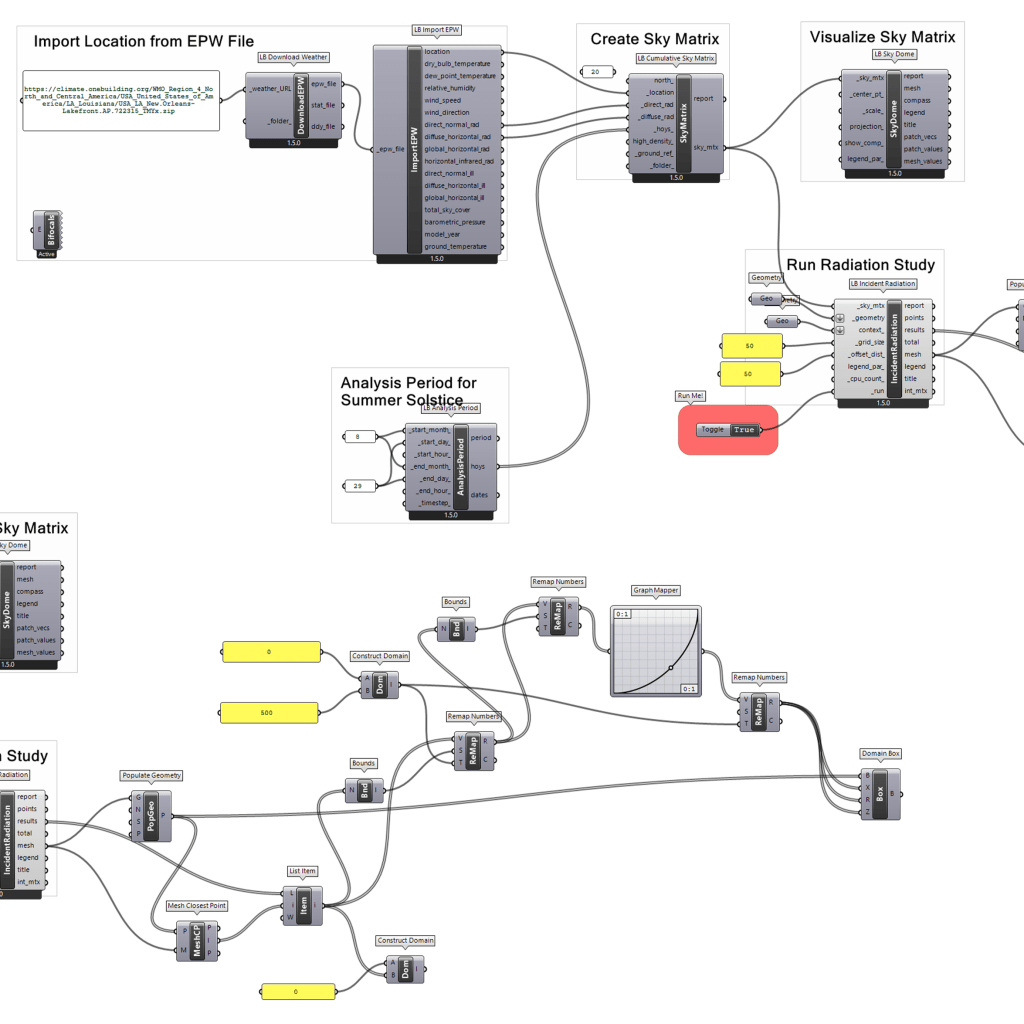

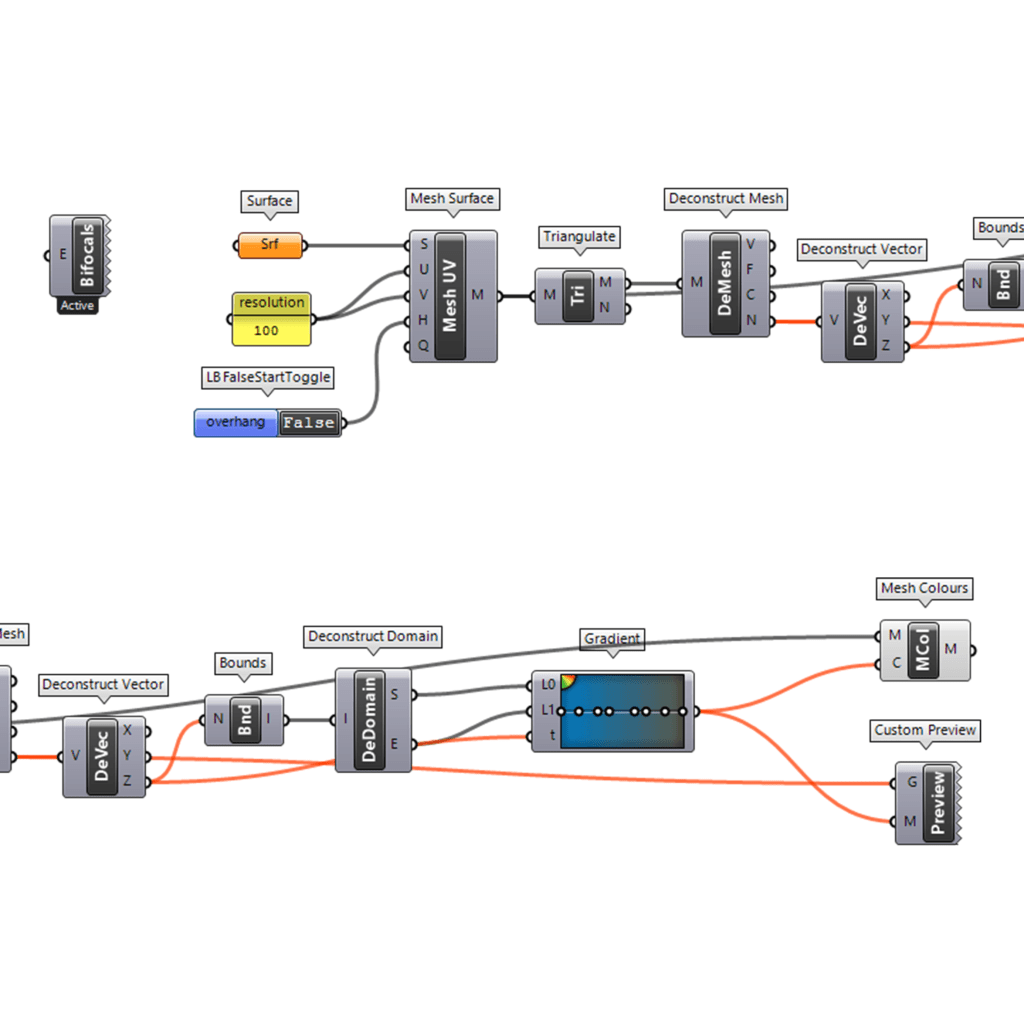

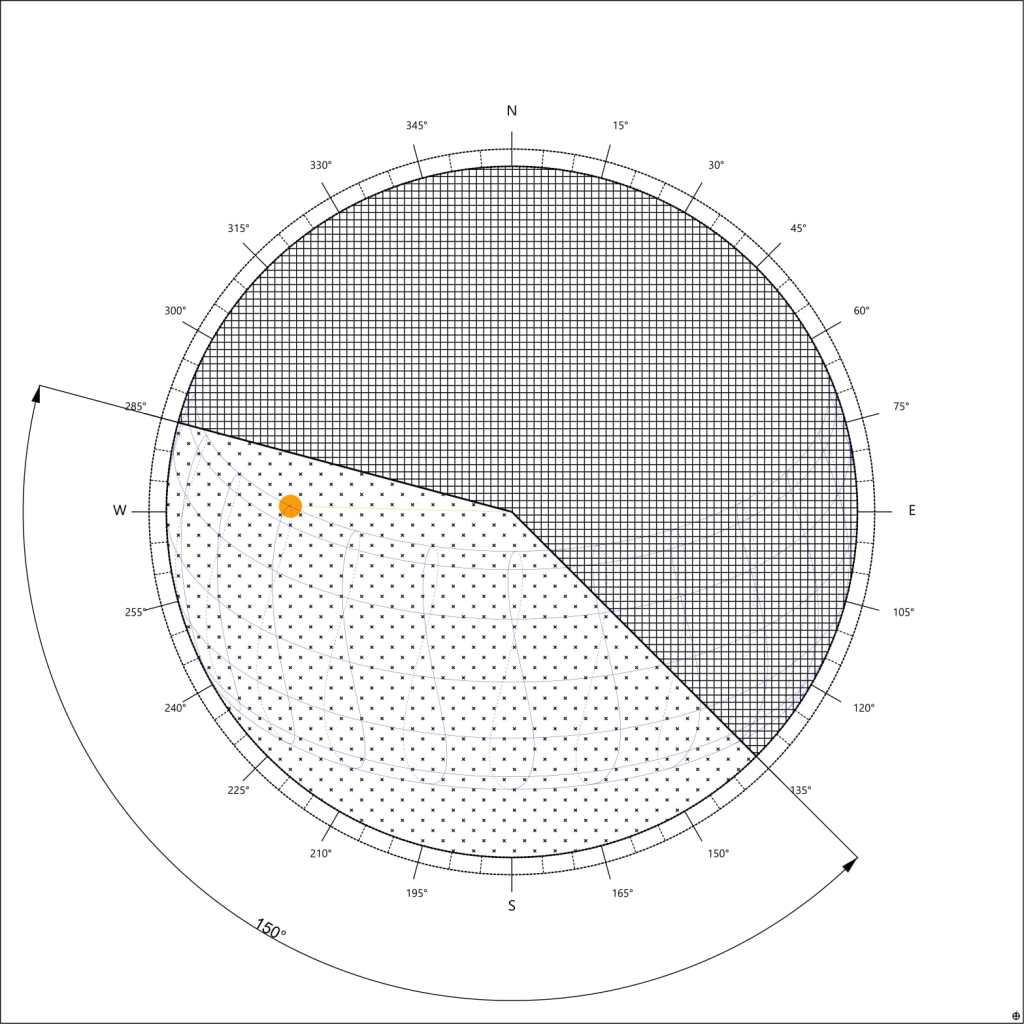

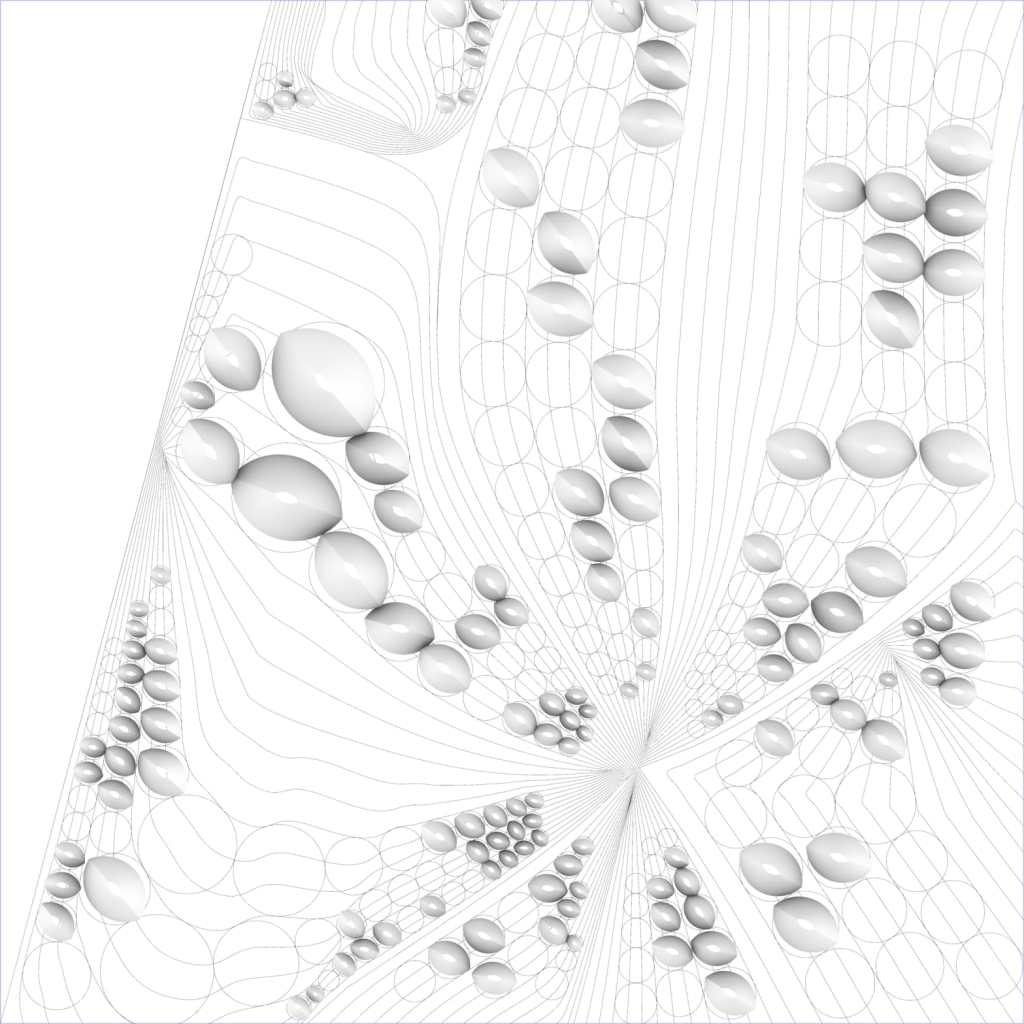

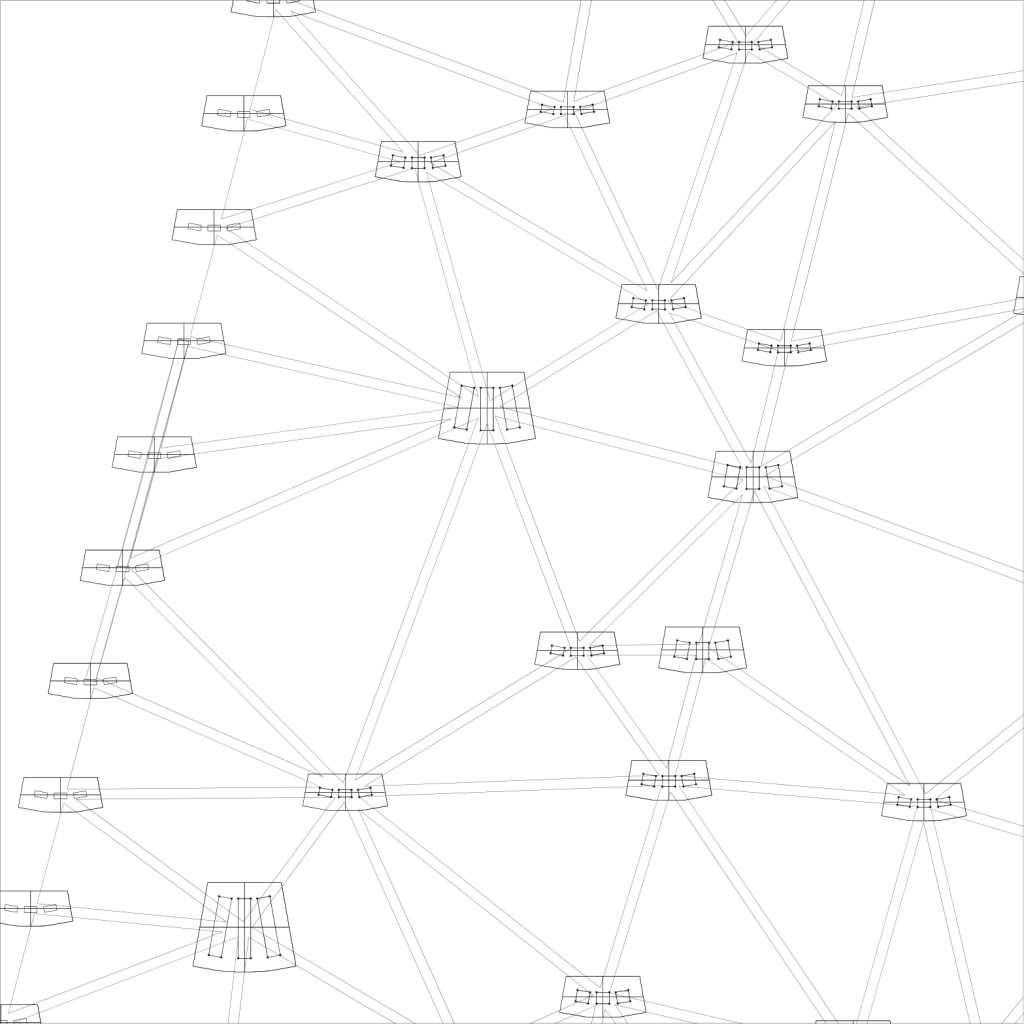

Reintroducing the forgotten indigenous intelligence requires an understanding of thermodynamic components that allows for the interrelationship between humanoid and the environment, as intrinsically intertwined with wellbeing. In the case of the lower 9th ward in New Orleans, its unique topography presents challenges for harnessing thermodynamic components. Located below sea level, this neighborhood is prone to disastrous events. By harnessing the sediments from the ancient river that flowed undisrupted, we can restore the ground to its original level. During the summer, prominent southernly winds can be harnessed for natural ventilation, while blocking cold northerly winds. New Orleans flat conditions create a challenge for solar trappings, whose locations can be indicated by a change in topography. The US Army Corps of Engineers has crystalized the lower 9th ward and enforced a majoritarian function, and by slowly dismantling the flooding infrastructure New Orleans can re-introduce its swamp, become resilient and embrace natural hydrological disasters. Researching into indigenous tribes from this area reveals many systems of how they live amongst hydrological disasters amongst elements of nature. Working in collaboration, water and earth organisms advance and recede to initiate sediments past the striated infrastructure. By dismantling the levees of the US Army Corps of Engineers, the lower 9th ward can replenish its land and raise its elevation towards safety. By utilizing the locks that connect Lake Pontchartrain to the Mississippi River, and strategically removing portions of the artificial levees minoritarian citizens can reintroduce hydro sediments into the landscape and re-grade the neighborhood to contain a system of mounds that work in conjunction with the topography. As a result, the lower 9th ward can revitalize itself. Protected from flooding through mounds, air organisms can harness southerly winds for passive cooling, and gives space above the datum providing safety. The introduction of mounds creates new opportunities for harnessing the sun, by utilizing the southwest facing slopes in order to further retain heat. As a whole, we envision the lower ninth ward to then breathe and operate Living safely within their community above sea level.

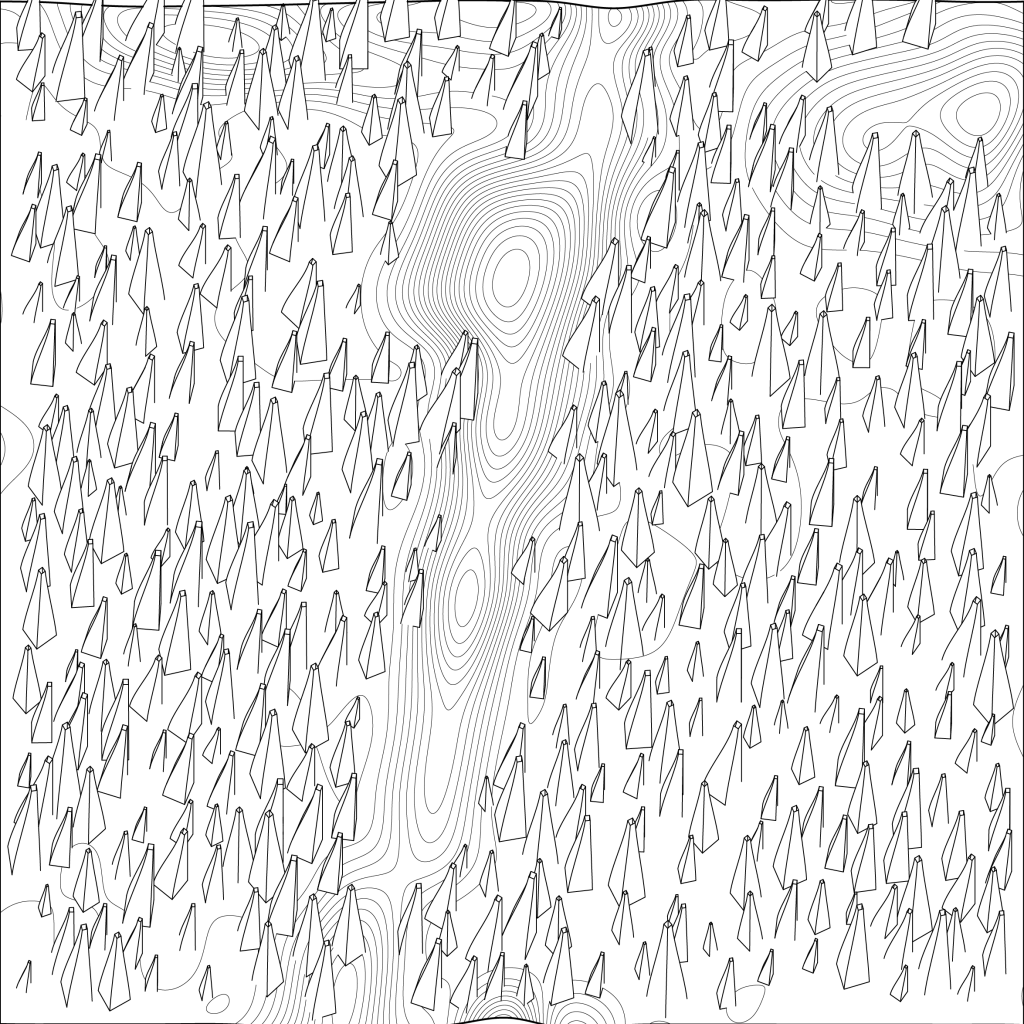

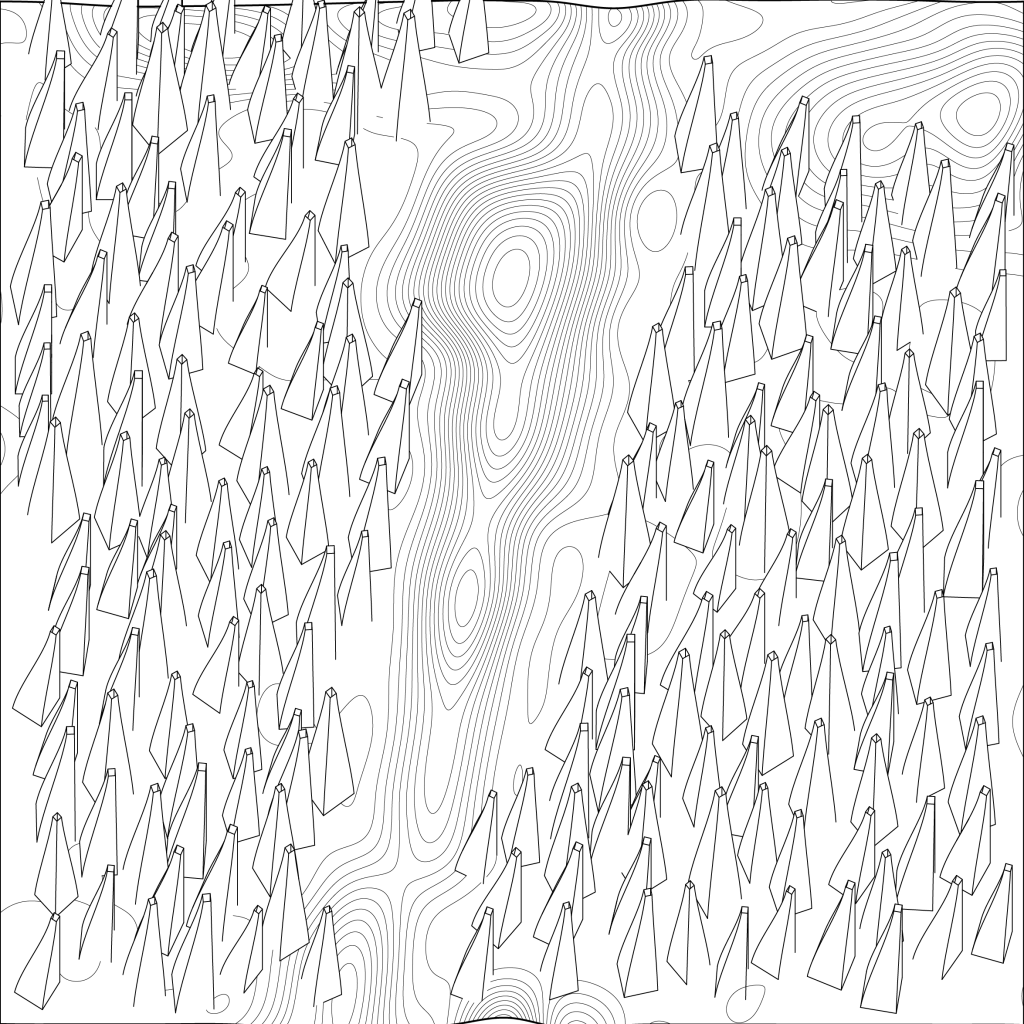

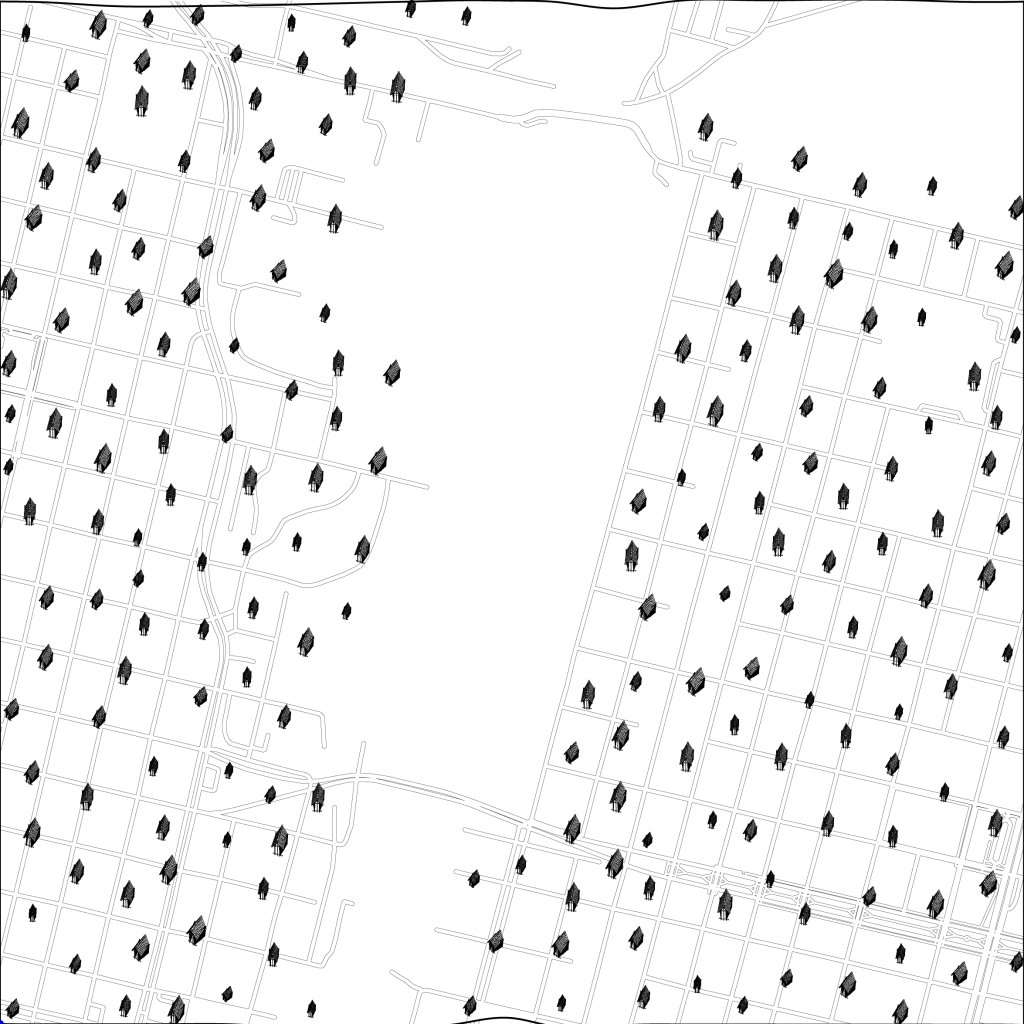

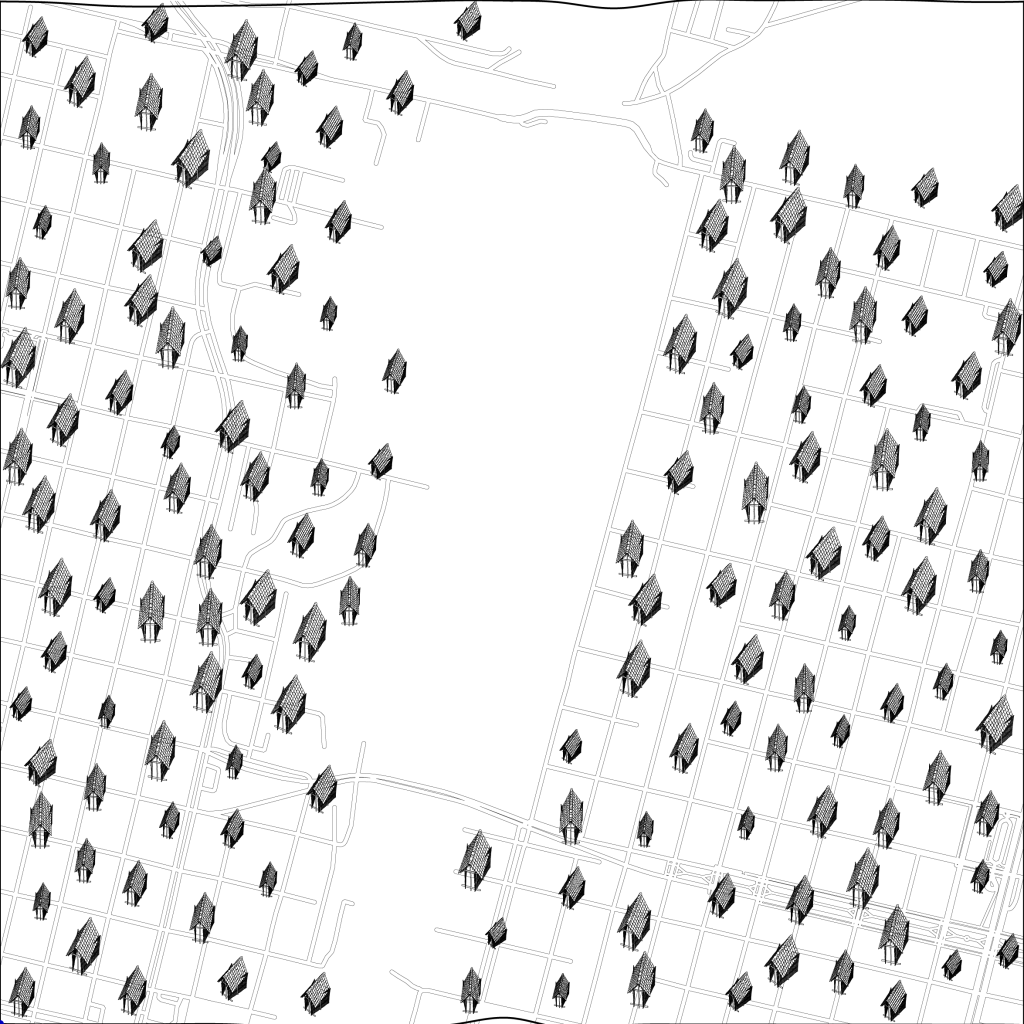

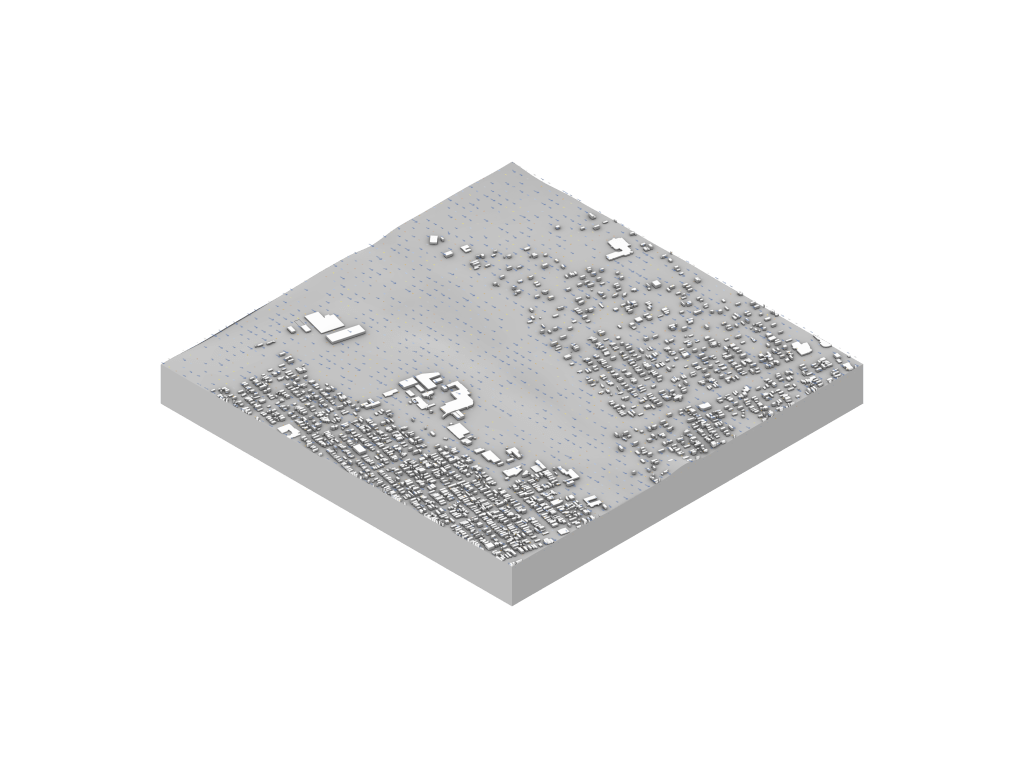

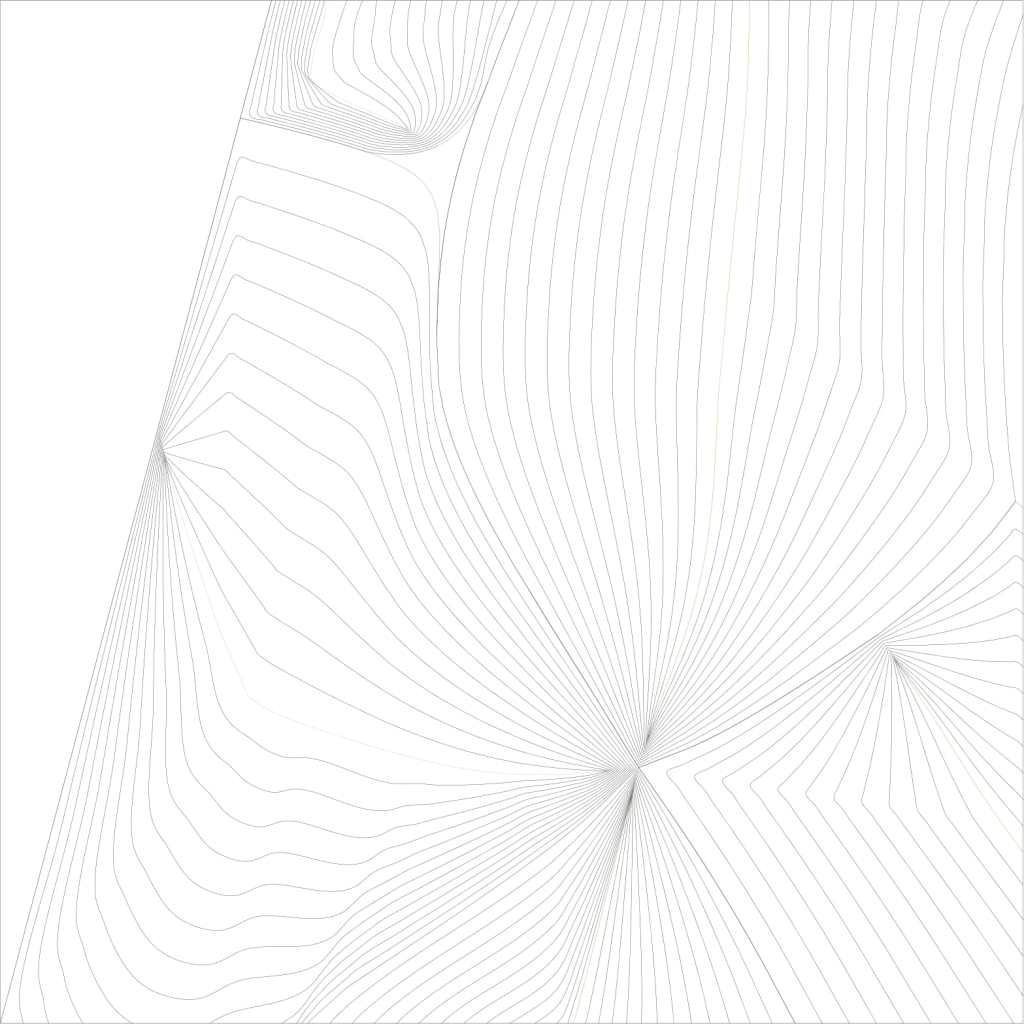

Post Katrina figure ground reveals population densities, evident of climate inequity. This density reflects elevation, with majoritarian watersheds occupying the high ground, leaving undesired real estate for the minor. To implement our intervention, a code of thermodynamic hierarchy must take place. It prioritizes water, earth, air and then fire Analyzing the small changes in the topography, we can identify positive and negative inflection points in the lower 9th ward. Tracing connections between positive and negative inflection points creates a model for the progression of our proposal. Saddle points in the landscape indicate locations for a minoritarian decentralized infrastructure. Positive inflection connections indicate the center of our mounds, while negative inflection connections create artificial rivers that will bring hydro sediments that make our mound building possible. Through repetitive flooding disasters, we can simulate topographical time steps for our mound building, starting from the rivers and moving their way towards the positive inflection points. As the mounds grow, fire organisms are added to accelerate the growth of our mounds by harnessing the energy of the sun in order to remove sediments from the water. Meanwhile, our air organism will offer the minoritarian citizens a safety line to survive future disasters. Utilizing post disaster foundation footprints, these air organisms will elevate the minor using stilts. Our intervention removes the levee infrastructure in the hopes of accelerating the disaster, and in turn retrieving the sediments that will allow New Orleans to rise back up to sea level. Meanwhile, minor dwellings are elevated to provide safety for the years to come. In turn, future disasters will restore the elevation of the lower 9th ward back up to sea level, which was present prior to the drainage of the swamp that created the present development. In conclusion our design team hopes to create tracings that highlight inequities created by the major state powers that have asserted their dominance on the landscape, with the intension of reversing major and minor power roles and establishing socioeconomic and environmental equity. In doing so, we run into the problem of tracing data that uses major language, and in turn diminishes the use of minor language. In application, this can lead to training artificial intelligence with racially biased data in a form of binary information that does not acknowledge intersectionality and the rhizomatic relationships that form the identities of individuals. Moreover, the data generated created by major literature does not acknowledge the environment and can in turn halt environmental justice. To design a system that embraces natural disasters and establishes equity, we must rediscover the ancient nomadic knowledge that is indigenous to the land and embrace the rhizomatic relationship between the land and the environment as intrinsically intertwined with human development and well-being.

Leave a comment